Durham Issues Scathing Response To Sussmann's Filing For Dismissal

Sussmann's Lie To General Counsel James Baker Was Directly Material To The FBI's Decision To Open An Investigation Into The Alfa Bank Hoax

It was February 17 that former Perkins Coie lawyer Michael Sussmann and his lawyers filed a motion to have the judge dismiss his indictment by Special Counsel John Durham.

Sussmann has been indicted by Durham for making a materially false statement that directly affected the FBI’s decisions in investigating an alleged connection between the Donald J. Trump Organization and the Russian-based Alfa Bank.

In that motion to dismiss, Sussmann argued that his lying to then-FBI General Counsel James Baker about not working for any client was immaterial to the FBI’s decision making process as to whether or not the agency opened up an investigation into the Alfa Bank allegations.

Today, March 4, 2022, Durham filed his response to the Sussmann legal team’s motion to dismiss. And what a response it was. He makes short work of Sussmann’s claims, but before I dive into that here’s a background refresher on where the Sussmann case currently stands:

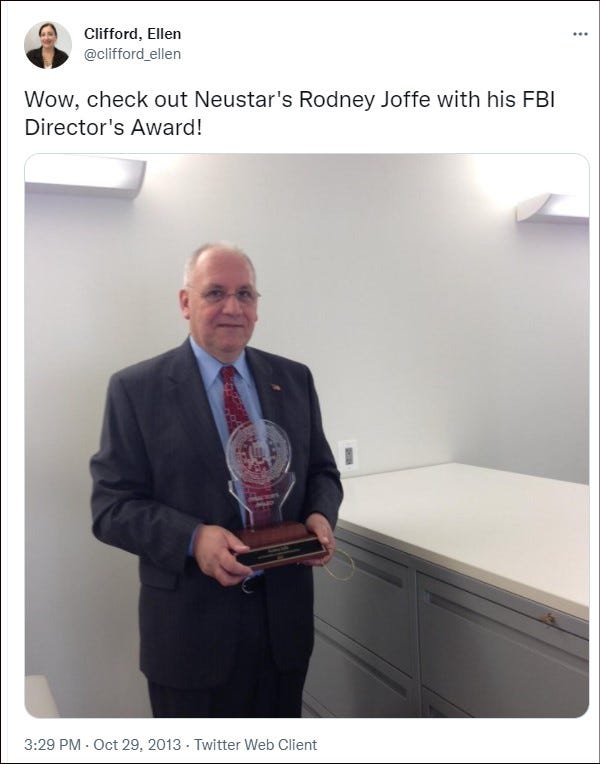

A lot of media heat and sound and fury was generated by Durham’s February 11 filing having revealing that former Neustar Vice-President Rodney Joffe & several Georgia Tech researchers had been exploiting their privileged access to federal databases - including dedicated servers for the Executive Office of the President - in order to mine them for non-public information and data on Trump and several of his close associates. The filing goes on to allege that Joffe and Co. were than taking this illegally mined data and handing it off to other members of the Hillary Clinton campaign team as well as other campaign operatives at the firms of Perkins Coie and Fusion GPS.

Durham’s claims he will establish in court should this case proceed to trial that this highly illegal data-mining activity began in July of 2016 [which happens to be when Clinton gave her approval to have the dirty trick operation go forward] and continued on past the 2016 presidential election into the transition between the Obama and Trump administrations, and then on into the Trump presidency itself once the real estate magnate had taken up residence inside the White House.

In fact, Durham details in that explosive filing made on February 11 that when Sussmann made his visit to “Federal Agency-2” in February of 2017, he handed off an updated version of the Alfa Bank Hoax that now included highly sensitive Executive Office of the President [EOP] data that the earlier FBI version of the hoax had not contained.

The Fake News Media then leaped into spin mode as it attempted to ‘explain’ that Durham’s filing didn’t say what it said.

Far from retreating from the claim that political operatives in the direct employ of the Clinton campaign team had been spying on the Executive Office of the President after Trump took up residence in the White House, Durham states it again in this latest filing.

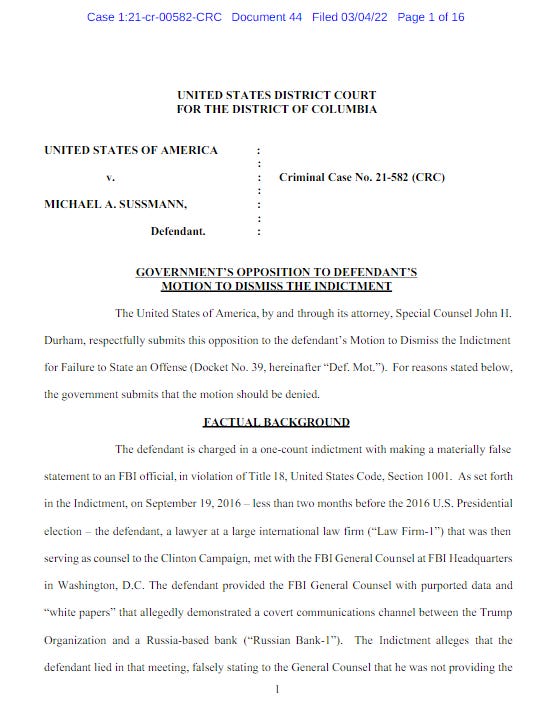

The first 3 pages of the filing:

The bottom section of page 2 and the top section of page 3 of the new Durham filing discuss how Joffe & Co. were illegally exploiting their federal database/server access for partisan political purposes. This illegally collected data then turns up in the updated Alfa Bank Hoax that Sussman hands off to the CIA in February 9, 2017.

Durham then demonstrates that part of the updated Alfa Bank Hoax data that Sussmann gave the CIA involved supposed evidence that Trump and his close associates were using “Russian-made wireless phones” in and around the White House. The obvious inference being that Trump and his White House team were getting their orders from the Kremlin over these particular Russian-made wireless phones.

It would stretch credulity to believe that Sussmann was claiming to the CIA that Trump and his team were getting their orders from Putin in close proximity to the White House over these Russian phones while Trump was yet merely a candidate for the Presidency. Since he was making this handoff of the updated and revised Alfa Bank Hoax to CIA officials on February 9, about two weeks after Donald J. Trump’s inauguration on January 20, 2017, it does certainly look like Sussmann is purporting to the federal agency that the Russian phone data was very recent and had been gathered since Trump’s administration had taken office.

Durham then discusses how Sussmann in making this approach to the CIA, once again told a material lie when he claimed he was not handing them this Alfa Bank Hoax on behalf of any client but that he was instead doing this on his own initiative.

Durham proceeds to demonstrate the materiality of Sussmann’s lie by discussing the meticulous billing records that Sussmann kept of all of his activity in helping to concoct and then disseminate the Alfa Bank hoax. The client Sussmann was billing for all of this activity from July of 2016 all the way through his approach to the CIA in February of 2017 was in fact the Hillary Clinton campaign. Had Sussmann disclosed this fact to the FBI or the CIA, it would have had a dramatic effect on the way those federal agencies handled the allegations he was proffering to them.

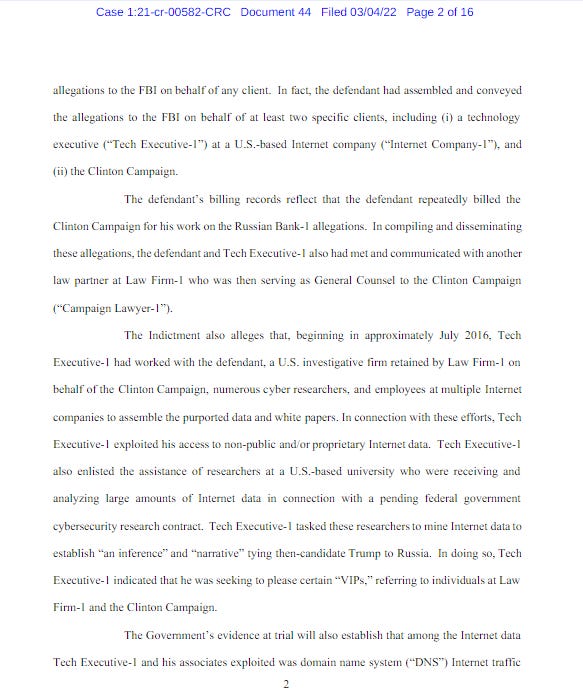

The next few pages of the Durham filing:

Sussmann and his lawyers are attempting to get U.S. District Court Judge Christopher Cooper to toss out Durham’s indictment by urging him to rule himself that Sussmann’s lie to Baker was immaterial. There are serious problems with this request.

Durham’s prosecution team counters this by pointing out how Sussmann’s lie not only was material to the FBI’s Alfa Bank investigation, but also how legal precedent has established that it’s up to the jury to decide the issue of materiality after the state has made it’s case at trial.

The Special Counsel’s Office points out that it was certainly a material fact that Sussmann was hiding from Baker that he was there on behalf of not just one but two clients, both of whom were paying him very well for the work he was doing on their behalf. Work that certainly included the approach he was making to Baker.

The Durham team quite ably points out that had Sussmann fessed up to the fact he was there on behalf of the Hillary Clinton campaign, this would indeed have influenced the subsequent FBI decision-making process about opening an investigation into the Trump campaign based on the fake evidence he was proffering to the agency.

The defendant’s false statement to the FBI General Counsel was plainly material because it misled the General Counsel about, among other things, the critical fact that the defendant was disseminating highly explosive allegations about a then-Presidential candidate on behalf of two specific clients, one of which was the opposing Presidential campaign. The defendant’s efforts to mislead the FBI in this manner during the height of a Presidential election season plainly could have influenced the FBI’s decision-making in any number of ways.

And later on in the filing, the Durham SCO returns to this point:

Accordingly, and contrary to the defendant’s argument that a tipster’s “motivation” is insignificant and “ancillary” (Def. Mot. at 15), the evidence at trial will demonstrate that a person’s motivation in providing information to the FBI can be a highly material fact in determining whether and how the FBI opens an investigation and then conducts an investigation it has opened. And the evidence will show that it would have been all the more material here because the defendant was providing this information on behalf of the Clinton Campaign less than two months prior to a hotly contested U.S. presidential election. In sum, the evidence will demonstrate that the defendant’s false statement to the FBI General Counsel had the capacity to influence the lawful function of the FBI as it related to the case initiation phase.

Exactly as I expected he would, Durham argues that had Sussmann informed the FBI's general counsel he was there on behalf of the other campaign in the presidential race, as well as on behalf of a cybersecurity expert the FBI was well acquainted with, that would have directly affected the FBI's decision about how to handle a prospective investigation into the allegations that Sussmann giving to them.

Note how Durham points out that Rodney Joffe didn’t want Sussmann using his name, or revealing him as one of the clients who was paying Sussmann to make this approach to the FBI and then the CIA:

For example, had the defendant truthfully disclosed the fact that he represented Tech Executive-1, the FBI likely would have asked certain questions and conducted interviews during the investigation that would bear directly upon the information’s reliability and/or Tech Executive-1’s motivation in providing the information.

Namely, as the defendant’s motion reveals (Def. Mot. at 18-19, fn. 8), Tech Executive-1 had a history of providing assistance to the FBI on cyber security matters, but decided in this instance to provide politically-charged allegations anonymously through the defendant and a law firm that was then-counsel to the Clinton Campaign. Given Tech Executive-1’s history of assistance to law enforcement, it would be material for the FBI to learn of the defendant’s lawyer-client relationship with Tech Executive-1 so that they could evaluate Tech Executive-1’s motivations. As an initial step, the FBI might have sought to interview Tech Executive-1. And that, in turn, might have revealed further information about Tech Executive-1’s coordination with individuals tied to the Clinton Campaign, his access to vast amounts of sensitive and/or proprietary internet data, and his tasking of cyber researchers working on a pending federal cybersecurity contract.

The Special Counsel’s Office then makes the very relevant point that in all the cases cited by the Sussmann legal defense team where a lie to a federal agency was ruled to have been immaterial, all those rulings came after the state had already made it’s case at trial, and that it was up to the jury to make the materiality determination.

The defendant cites to multiple cases where the Supreme Court and Circuit Courts have held that the false statements and misrepresentations at issue were immaterial as a matter of law. See Def. Mot. at 7-10. But critically, all of those cases involved post-conviction appeals or motions to vacate the conviction after the Government presented its case at trial. Accordingly, none of these cases support the defendant’s requested relief here – that is, that the court dismiss the Indictment before trial because it fails to sufficiently allege that the defendant’s false statement is material. What the cases do show is that courts have routinely declined to usurp the jury’s role in making the determination on whether a false statement is material. [emphasis added]

Durham then demonstrates that these after-the-fact rulings once the gov't had presented it case all found the lie told by the defendant couldn't have affected the federal agencies decision making because no decision-maker was aware of them.

For example, in United States v. Camick , the Tenth Circuit reversed a Section 1001 conviction upon finding that the statements at issue were not material because the relevant government decision-making body, the Patent and Trademark Office (“PTO”), never saw or reviewed the filing which contained them.796 F.3d 1206, 1218 (10th Cir. 2015). As a result, the false statements were immaterial because it was impossible for any decision by the PTO to be affected.

In the Second Circuit’s decision in United States v. Litvak, the court likewise reversed a jury trial conviction for false statements because the defendant’s misstatements in residential mortgage-backed securities transactions were not capable of influencing any decisions of the U.S. Treasury. 808 F.3d 160, 172 (2d Cir. 2015).

And in United States v. Naserkhaki, the court there held that one of two false statements contained in a defendant’s application for refugee travel documents was immaterial because it related “to anancillary, non-determinative fact,” specifically, the fact that the defendant had failed to inform the agency that he had submitted a prior application for the travel documents. 722 F. Supp. 242, 248(E.D. Va. 1989).

Durham demonstrates how those three examples of lies that never influenced any federal decision-making are in stark contrast to what Sussmann did, stating his lie about not representing any client right to the FBI general counsel's face in his office at FBI HQ.

In contrast, the defendant made his false statement directly to the FBI General Counsel on a matter that was anything but ancillary: namely, the existence vel non of attorney-client relationships that would have shed critical light on the origins of the allegations at issue.

Sussmann and his legal team then try the novel defense that even though Sussmann lied about not representing any clients paying him to go to the FBI and hand off the Alfa Bank Hoax, the FBI and Baker knew Sussmann represented the DNC, so they should have known without Sussmann having to volunteer it that he was there for a politically motivated client and if they didn't bother to ask him about that well too bad.

Durham counters by pointing out that Baker knew Sussmann worked for the DNC as a cybersecurity lawyer due to the recent 'hacking' of the DNC emails. That did not mean that Baker should have guessed that Sussmann was also a private operative for the Clinton campaign or Rodney Joffe.

"It was fine for me to lie to FBI General Counsel James Baker about how I was working for the Hillary Clinton campaign when I approached him with this Alfa Bank hoax because he already knew I was working for the DNC!" is one of the dumbest arguments Sussmann could have made, yet he tried it. Durham makes short work of it.

In an effort to downplay the materiality of this false statement, the defendant asserts that the FBI General Counsel was aware that the defendant represented the DNC. But the Government expects that evidence at trial will establish that the FBI General Counsel was aware that the defendant represented the DNC on cybersecurity matters arising from the Russian government’s hack of its emails, not that he provided political advice or was participating in the Clinton Campaign’s opposition research efforts.

Indeed, the defendant held himself out to the public as an experienced national security and cybersecurity lawyer, not an election lawyer or political consultant. Accordingly, when the defendant disclaimed any client relationships at his meeting with the FBI General Counsel, this served to lull the General Counsel into the mistaken, yet highly material belief that the defendant lacked political motivations for his work.

Based on my reading of the filing, it’s hard to see how Judge Cooper could agree that Sussmann’s deliberate lie to hide who was paying him to approach the FBI with this stupid hoax was immaterial.

I do not see him dismissing the indictment.

This latest Substack column is brought to you by Resist The Mainstream. RTM is a new website dedicated to covering the news and events that the mainstream media ignores or attempts to suppress. I am now on the editorial staff there.

You can also check out One Source Solutions, a great payment processor site run by and for patriots. Tired of cancel culture and worried about getting deplatformed by PayPal or some other Silicone Valley website? Here’s your answer. Be sure to tell them Brian sent ya!

To support my independent journalism, you can also make a donation of any size to my Venmo, CashApp or PayPal accounts.

And I thank you for your support. :)

It takes a very special person to to diligently dig through documents like this and get to the real meat. If you're looking for unbiased truth in reporting, Brian is a one stop shop.

Thank You again Brian👏🙏